Illegal Palm Oil’s Route to Sweden

On site inside an Indonesian rain forest, Sveriges Natur uncovers clear evidence: Sweden’s largest producer of plant-based oils and fats for use in consumer goods, AAK, is concealing business dealings that threaten both the forest and its wildlife. AAK buys palm oil from at least 20 mills that source their fruit from illegal plantations located inside a protected nature reserve.

As it narrows, the condition of the road we are travelling on steadily worsens. Every now and again, our driver is forced to stop and climb out of our vehicle to assess how best to parry the many craters in the road.

It is a dry, gravelled road bordered on both sides by a tangle of dense vegetation worthy of our location: we are deep in the heart of the jungle on the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

Here on the fringes of Tesso Nilo, one of Indonesia’s largest national parks, live tigers, orangutans and venomous snakes, though we are unlikely to catch a glimpse of any.

“They’re endangered species,” explains our fixer, who is helping Sveriges Natur gain access to the area in secret.

We soon pass through a tiny village that doesn’t even show up in our vehicle’s GPS navigation system. A number of trucks stand parked along the side of the road.

Our fixer warns us not to stop and exit our vehicle. Doing so is far too dangerous, since the activity going on here is illegal.

The trucks standing along the roadside are waiting in line to ascend onto large loading docks. Once in position, they will be filled to capacity with palm fruit grown and harvested illegally inside the national park only a stone’s throw from here. These dock, or collection sites, number 27 in all.

We have reached the hub of Indonesia’s illicit palm oil trade – a business far larger in scale than what many other investigations have succeeded in uncovering.

High demand drives illegal forest clearing

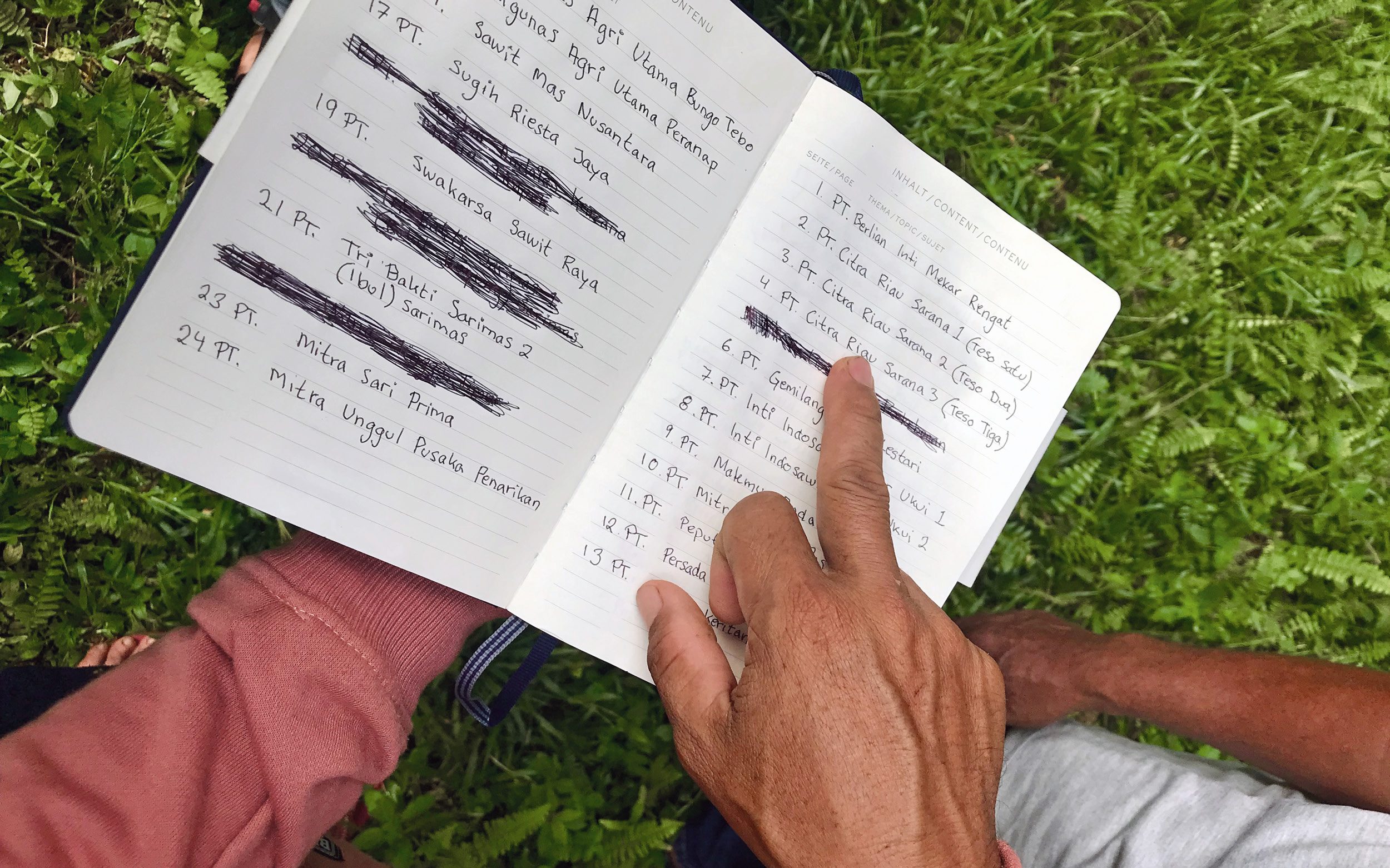

Sveriges Natur’s reporter is armed with a list of 20 mills that extract oil from illegally-grown palm fruit, which is then shipped to customers worldwide. Each mill supplies palm oil to a slew of international businesses, including Swedish-Danish company AAK (formerly AarhusKarlshamn AB). AAK is Sweden’s largest producer of plant-based oils and fats for use in consumer goods, including many common grocery items sold both in Sweden and abroad.

When an article published three years ago in Swedish daily Expressen revealed that AAK had bought palm oil milled from fruit farmed illegally inside Tesso Nilo, company president and CEO Johan Westman dismissed the allegation:

“We have a long history of systematic initiatives aimed at preventing forest clearing by operators within our supply chain. On the other hand, it’s not possible to fully guarantee that individual stakeholders aren’t disregarding the standards we’ve agreed on,” Westman told Swedish newspaper Dagens Industri.

Related article: Swedish Asset Management Firms Back AAK Despite Illegal Palm-oil Dealings

Waving away any suggestion of wrongdoing, Westman spoke enthusiastically about AAK’s sustainability work and gave assurances that the company would immediately enact the measures necessary to halt the flow of illegal palm oil in its supply chain.

For years, the palm oil industry has boasted about its environmental certifications and guarantees of responsible sourcing. Like practically all companies concerned, AAK publicly denounces palm oil originating from plantations that destroy rain forest, but when Sveriges Natur reviewed the company’s registered raw material suppliers based in Indonesia, it found that three of four lack the industry’s own RSPO sustainability certification (see fact box).

Satellite imaging makes it possible to track the progress of systematic deforestation in Indonesia. According to the organisation Global Forest Watch, which uses imaging and other monitoring tools, more than 28 million hectares (> 108,000 sq mi) of forest have been cleared in Indonesia – the world’s largest producer of palm oil – over the past 15 years. The resulting loss of their jungle habitat has caused animal species such as orangutans, tigers and elephants to become seriously endangered.

”The demand is sky-high”

The tiny village of Bukit Kusuma lies on the edge of Tesso Nilo National Park. A total ban on palm oil trading was introduced both here and in other areas of the park in 2016 in an attempt to protect what remains of Tesso Nilo’s rain forest.

“But nobody cares about that,” explains a man who has worked selling palm fruit from Bukit Kusuma for more than 30 years. “Selling palm oil grown inside the park is big business,” he explains.

This man declines to go on record as a source, citing concerns about his personal safety. What he is willing to disclose is that he owns several trucks and earns his living by supplying nearby mills with illegally-harvested palm fruit, which he buys from collection sites in Bukit Kusuma. He describes himself as one of the region’s “palm-fruit middlemen”.

“Everyone around here knows that the palm fruit in Bukit Kusuma is illegally harvested inside the national park,” he says.

The oil derived from this illegal fruit is traded within an extensive sales chain, making it difficult to trace its exact origin. Trucks transport the illegal fruit to the collection sites, where it is mixed with legally-grown fruit harvested from other plantations in the region, after which the entire cargo is forwarded to nearby mills. From these mills, the extracted palm oil is hauled to major shipping ports where it is loaded onto cargo vessels bound for buyers in the international market.

According to the same middleman with whom we spoke, international palm oil companies don’t know how their own supply chains function at the production level.

“If they knew, no palm fruit from Bukit Kusuma could ever be sold at all. But the reality is just the opposite: demand is sky-high,” he reveals.

He explains that the volume of illegally-grown palm fruit is so great in relation to legally-grown fruit that he always turns a bigger profit by buying from the collection sites at Bukit Kusuma even though these are farther away than other collection sites.

“To keep the amount you spend on gas down, it’s preferable to buy your entire load of cargo from the same collection site. That makes the illegally-harvested palm fruit from Bukit Kusuma the best alternative,” he explains.

Related article: Food Industry Giants Use Illegal Palm Oil

This information is confirmed by the owner of a legal collection site located in the neighbouring village of Pangkalan Gondai.

“It’s totally impossible for us to compete with the kind of volumes that sellers of illegally-harvested palm fruit can provide,” he says.

He informs us that palm fruit from Bukit Kusuma is currently selling at around USD 0.15 per kilogram. The average price for legally-grown palm fruit sourced from nearby plantations is generally just under USD 0.02 more expensive per kilogram.

During the harvest season, there is a constant, round-the-clock flow of trucks loaded with palm fruit departing from Bukit Kusuma. Concealed from view in a hiding place and under the cover of darkness, Sveriges Natur’s reporter counts 13 fully-loaded trucks in the space of just 30 minutes.

The smaller lorries can carry 12 tonnes (approx. 26,500 lbs.) of fruit. The larger, 35 tonnes (> 77,000 lbs.). In total, 202 tonnes (> 445,300 lbs.) of palm fruit leave this village during the 30 minutes in which Sveriges Natur’s reporter is watching. At this rate, this amounts to almost 10,000 tonnes (> 22 million lbs.) of palm fruit hauled away in just 24 hours.

To see where these trucks are headed, Sveriges Natur’s reporter tails one of them along a dusty, gravelled road. After approximately 45 minutes, the trucks arrives outside the closed entrance to what looks like an abandoned factory site. Ten or so trucks wait in line outside the entrance. A sign shows the name of one of the mills on our list: PT Mitrasari Prima.

The security guards on duty eye our car suspiciously, so our fixer gets out and pretends to withdraw money from an ATM a little way away. While he is doing so, the entrance to the mill opens and the trucks drive in to unload their cargo of fruit.

Authorities turn a blind eye

We conduct our interview inside an area marked with a sign that reads “No unauthorised access”. The plantation owner reveals that his palms grow on around 300 hectares (1.15 sq mi) located inside Tesso Nilo.

He personally owns only 80 hectares (0.3 sq mi) of this plantation, and is paid by the owner of the remaining 220 hectares (0.85 sq mi) to manage his land too. He tells us that the other owner is a wealthy man from the capital, Jakarta.

The reality is that many owners of plantations in this area belong to the upper echelons of Indonesian society, and often have strong ties to both the government and the police. According to a local investigator working for Greenpeace, the palm oil trade originating in Tesso Nilo is only possible because of widespread corruption.

The local plantation owner explains that he can harvest 2.5 tonnes of palm fruit per hectare (> 5,500 lbs./0.004 sq mi) during the peak season. On a good day, trucks deliver his produce to the mills 3–4 times a day.

Harvesting is hard work, though. Between 6 a.m. and late afternoon, his labourers strive to harvest as much fruit as possible before the truck returns to pick up its load for sale to the mills.

To gather in the crop, these young workers move between the tall palms, using long sticks with sharp, curved blades attached to one end to sever the root of each hanging fruit. Each palm tree bears multiple clusters of fruit, and severing the root of each fruit takes a minute or two. One after another, the fruit falls to the ground.

Once the fruit has fallen, it is loaded onto a wheelbarrow that is moved from tree to tree until it is full, after which it is emptied at the edge of the plantation.

“We gather the harvested fruit by the roadside to make it easier for the trucks to collect it. We aim to fill at least one truck per day with 10–15 tonnes (22,000–33,000 lbs.) of fruit,” the plantation owner tells us.

He confirms that each of the 20 mills on Sveriges Natur’s list sells palm oil milled from fruit grown on his illegal plantation in Tesso Nilo.

“Selling palm fruit grown inside the national park to any one of these mills is no problem at all. If anyone tells you different, they’re lying,” he says.

He also informs us that relations between the plantation owners and palm oil mills in the region are good. The buyers at these mills know exactly where the fruit comes from.

But that hasn’t always been the case. Just five years ago, selling his fruit was a struggle, our source confides. Back then, explicit regulations and guidelines were in place that forced mills to reject any illegally-harvested palm fruit. Clear warning signs were erected across the region stating that trading in palm fruit harvested in Tesso Nilo was prohibited.

“We were forced to travel far from the region to be able to sell anything at all from our harvests. It was a costly, barely viable business,” he laments.

Then global demand increased.

“The mills were in such dire need of our fruit that, in the end, it became impossible for them to turn our consignments away,” he explains

The plantation owner shows us text messages sent between himself and a number of mills on his cell phone. These reveal an ongoing, secret bidding war between AAK’s raw material suppliers for the right to buy his illegal palm fruit. One after the other, in message after message, these mills raise their prices to match each other’s bids.

The owner also shows us a receipt issued by the PT Mitrasari mill. Besides the details of the purchase itself, the receipt bears both a signature and the mill’s own stamp. The owner admits that he holds out no hope for the future protection of the rain forest inside the national park. The demand for palm oil is simply too great.

“New plantations pop up inside the park all the time. There seems to be no limit to how much forest is allowed to disappear,” he says.

The companies know they are buying illegal goods

An executive at one of the mills included on Sveriges Natur’s list suggests to us that there is no chance of any mill rejecting palm fruit from Tesso Nilo. He is responsible for the quality control of the palm fruit purchased by his mill and, like many of our sources, prefers to remain anonymous for reasons of personal safety.

He also confirms that all of the mills on our list receive palm fruit from protected areas where its cultivation and harvesting is prohibited. For them, it is simply a matter of necessity in meeting the international demand for palm oil. Lending credence to the inspector’s account, outside the mill where he works an endless line of trucks waits to unload their palm fruit at all hours of the day and night.

He also tells us that international palm oil companies’ claims that they monitor their production chains are untrue.

“If that were the case, we would never be able to send a large volume of the palm oil we produce to market. These companies are well aware that they’re buying illegal palm oil, but they deliberately turn a blind eye to the issue,” he confesses.

While the inspector doesn’t know precisely how much palm fruit harvested inside the national park he buys each day, there is no question that the volumes are substantial. In fact, hundreds of trucks constantly travel back and forth between Tesso Nilo and his mill.

“If the world wants palm oil in so many of its products, people need to understand that the environment will pay the price. That’s the ugly truth of the matter. There is no alternative,” he admits.

Since many sources with whom Sveriges Natur spoke in preparing this report requested anonymity, our reporter contacted one additional owner, Jamaluddin, from a collection site in Bukit Kusuma, and a middleman, Randi Arkhan, who buys and transports illegally-grown palm fruit for sale to mills included on Sveriges Natur’s list. Both sources confirmed the veracity of the information presented in our report.

AAK: “We have 100-per-cent traceability”

When Sveriges Natur reached out to AAK for comment, the company’s President of Global Sourcing & Trading and Sustainability, Tim Stephenson, claimed that AAK maintains 100-per-cent traceability concerning all palm oil originating from the Tesso Nilo area.

While AAK is keen to advertise its sustainability work, as this report shows, the company is clearly procuring palm oil from mills that press fruit from illegal plantations located inside Tesso Nilo National Park.

Stephenson also maintains that AAK does not purchase palm oil directly from all of its suppliers and that, consequently, he does not possess information concerning the complete supply chain running to and from each individual mill. Both Stephenson and AAK’s Head of IR & Corporate Communications, Carl Ahlgren, request that Sveriges Natur send them the list of mills it has investigated, so that AAK can “review its work” with these suppliers.

It is also evident that AAK has neither severed ties with nor made efforts to improve the situation at any of the mills mentioned in an article published in Expressen now three years ago. These same suppliers – Segati (PT Mitra Unggul Pusaka), Peranap (Asian Agri, formarly Rigunas Agri Utama), Ukui I and Ukui II (Asian Agri) – remain on the list of mills investigated by Sveriges Natur this year.

Of the 20 discredited mills about which Sveriges Natur has information, only one is included on AAK’s blacklist of mills and suppliers audited by the company. To date, two mills are listed as having undergone auditing.

“While I don’t have any information on these particular mills, we do need to play an active role in supporting their efforts to improve, so that we can help local smallholders take steps in the right direction,” says Stephenson.

AAK declines to assume greater responsibility than this, claiming instead that it is better that growers and mills who trade in the illegally-grown palm fruit that is endangering the rainforest sell their goods to AAK, since AAK is more responsible than other companies, according to Stephenson.

AAK’s stated ambition is to “transform the palm oil industry, making it completely deforestation-free”. Indeed, the company has set itself the internal goal of achieving a completely deforestation-free supply chain by 2025. A reasonable goal, Stephenson believes, despite the obvious challenges that Sveriges Natur has uncovered.

After this report went to press, AAK claimed in an e-mail sent to the Swedish TT News Agency that Stephenson was misquoted. (Read the TT article published in newspaper Aftonbladet here.) That is not the case. The following is a transcript of the sections of our interview with Stephenson in which he states that AAK maintains 100-per-cent traceability for palm oil originating in the Tesso Nilo area. (Original, English-language transcript.)

Sveriges Natur: Sveriges Natur [and I] have followed an illegal trade of palm [fruit] from the nature reserve Tesso Nilo, which you probably know about, to various mills in the region. And our investigation on site shows that at least 20 mills [among] your suppliers are dealing with palm [fruit] harvested in this nature reserve. Do you know about these mills [that] are using palm [fruit] that has been harvested on land that is supposed to be rainforest?

Tim Stephenson: Of course, we don’t know which mills you are referring to specifically, because you have not shared that with us at the moment. But when we get any information related to new allegations, we will deal with [it] as we do with all our grievances and follow that through. We knew since your last article [article published in Expressen] we are not working in that area, we have obtained, have got 100-per-cent traceability to plantation within that area, so we know where it is coming from.

Sveriges Natur returns to this point later in the interview to confirm Stephenson’s earlier comments:

Sveriges Natur: And you said you have 100-per-cent traceability around Tesso Nilo, correct?

AAK’s Head of IR & Corporate Communications, Carl Ahlgren, interjects here: “To mills. Right, Tim?”

Tim Stephenson: Yes, definitely to mills, but I think they have confirmed to us that it is traceable. But we don’t maintain every link to every smallholder. But we are advised by our tier-1 smallholder that there [is] traceability to plantation. Particularly since Tesso Nilo is a special case to the natural reserve, right.

Translated to English by: Tanya Henriksson.